In a recent school visit associated with the Voices of the Future project, I worked with a group of colleagues including Susannah Gill from Mersey Forest to deliver a session which aims to develop a child-led manifesto for the environment. The manifesto is developed with 90 children in Year (5) and it targets different types of audience including the media.

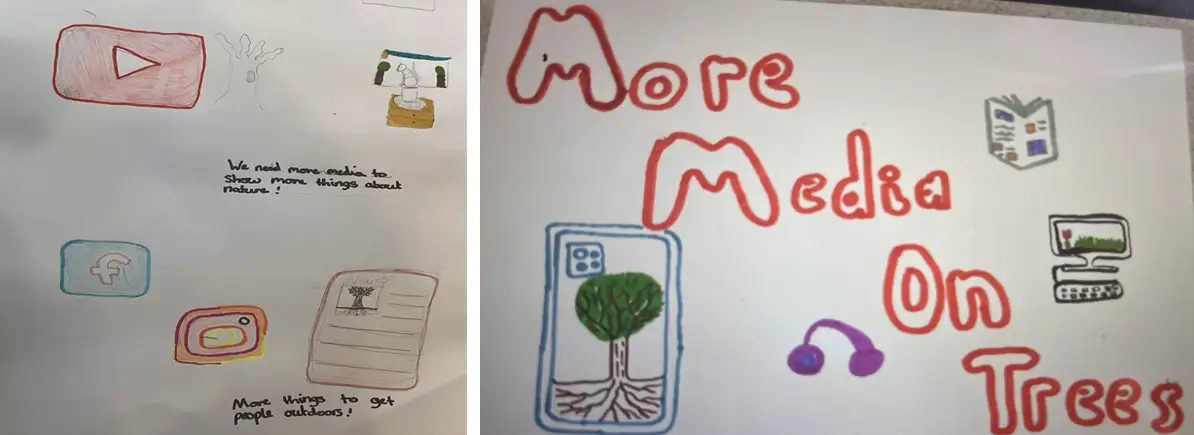

When we asked the children to think about some changes they’d like to see to the media as part of the manifesto work, we didn’t specify what the term means because we were particularly interested in tracing children’s interpretations of what counts as ‘media’ based on their own media consumption. Having reviewed relevant posters, it seems that the word ‘media’ for most children refers to a combination of traditional media (TV and newspapers) and social media as can be seen in the drawings below:

The messages from these drawings are clear. Children are interested in more programmes, videos, games, articles, online activities and mobile apps about nature, trees, and animals.

What is the relationship between the online and the offline when it comes to environmental education, being in/with nature, and engagement in climate action? This is a question that we have been puzzling about in the Digital Voices of the Future project. Without asking this explicitly, the Year (5) children on the Voices of the Future project provided some interesting insights through the drawings and messages produced as part of the manifesto activity:

This message draws a direct link between online exposure to trees on mobile apps and offline tree planting activities. The message assigns ‘the online’ a key role to do with raising awareness, building worldviews and influencing behaviour. These connections are present in my own work (Badwan, 2021) as an applied linguist interested in links between cultural consumption, worldviews, and behaviour. To explain this in simple terms, the stories we are used to hearing and the discourses that we internalise due to their dominance are central to the formation of worldviews, storying, and counter-storying. This means that the media that the children consume is part of their own world-making. Posthuman and new materialist theories contribute to this discussion by asserting that individuals are embedded and embodied in material conditions, including digital ones. For example, Kell (2015) maintains that things ‘make people happen’ in a statement that indicates the influence that material things have on how people think about certain things or behave towards certain events. This extends to digital influences as well.

What the children tell us in these drawings is that they do not have enough exposure to opportunities that engender their relationship with nature. These opportunities are not just related to programmes and articles where information flows in one direction. Rather, they entail interactive opportunities through video games about trees as the next drawing tells us:

The ask here seems simple: Make more games about trees that are educational and fun. This is the mission that the Digital Voices of the Future project seeks to achieve. The next few months will be exciting for the Digital Voices team as we work on developing a game that speaks to children’s imagined characters, trees, landscapes, worlds, dynamic actions, among many other unfolding dimensions which seem to not only entertain but also educate- in a different way.

References

Badwan, K. (2021). Language in a Globalised World: Social Justice Perspectives on Mobility and Contact. Palgrave McMillan.

Kell, C. (2015). “Making people happen”: Materiality and movement in meaning-making trajectories. Social Semiotics, 25, 423–445

want to find out more about our courses?

If you have a curiosity about the natural world, wish to pursue a career in science, or spend your future working in the great outdoors - we have some ideal course options to get you started.

.jpg)